Interview with Sascha Pohflepp

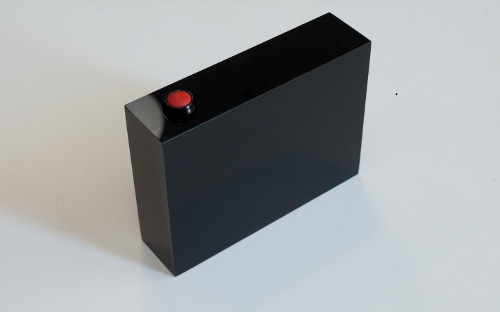

Sascha Pohflepp studied at the Berlin University of Arts (UDK). As part of his final dissertation at UDK, in 2006, he created Buttons, an artwork that is featured in the White Room in Nervous Systems. Buttons is a “camera without a lens”: pressing the shutter captures a time stamp, not an image, sends this time stamp to Flickr, the photo-sharing site, and searches for an image taken at the very same time - an image then returned to the 'photographer'.

In this interview, Sascha spoke to Maya Ganesh from Tactical Tech about his work, and the past, present and future of image-making and photography.

Could you tell us about Buttons and where it comes from? What was the inspiration for this work? This project was first created in 2006 as part of a degree at the Digital Media class of the Berlin University of the Arts. At that time the photo sharing site Flickr was relatively popular. In essence, Buttons is a camera yet it doesn't take a photo, it rather takes a time-stamp and it uses this metadata to look for uploaded images with the same time-stamp. In doing so it creates a weak link between different users of the same technology - both were doing the same thing at the same time, pressing a button. It's a bit romantic I suppose…my younger self was a bit romantic.

But what Buttons really does, or is trying to do, is to suggest that with sites like Flickr, photography is moving from being a memory technique toward being something else, a communication technique. What changes when you go from taking a photograph to remember your holiday, to sharing it with many people, potentially everybody? Now such photographs have changed yet again through turning the camera around and taking pictures of oneself.

It adds another layer, doesn't it, when what is supposed to be a carefully crafted moment of individuality is reduced to its metadata. So what happens then? Well, a selfie, according to Buttons, is metadata just like any image. so it treats it the same way. It is a good example of something I have not really talked about much, which is that, at some level, you are possibly never really taking a photograph. You are not image-making, you are recording metadata. Which leads to the other, deeper point that photography by now is actually a fully realized networked practice. Ten years ago some were very critical of this claim I made; people who weren't thinking about photography as part of the network and were more concerned with the increased ease of taking images. Photography as a networked practice now exists to the point where, especially in popular use, the value of the communication value of a photo has outstripped the memory value of photographs. Look at Snapchat for example, which is an explicit communication technique, not a memory technique, all based on images. And there is Instagram of course. Those are not image-making practices but networked communication techniques that are used billions of times per day. This is a definite shift in the history of photography.

Julian Bleecker, a mobile phone designer and who taught at the University of Southern California had at the time referred to Buttons as a 'blind camera’ which not only means that it does not have optics but, inversely, that the network has become part of the visual apparatus.

So photography is an evolving practice; can you trace some more of this evolution both in the past, and the future, as you see it? You could say that 'photography' as we know it is a series of image-making techniques using light, technical devices and human perception. Maybe there never was such thing as photography. What I mean is that you can look at practices that photography came from, like the camera lucida and the camera obscura, which photography has historically evolved from. These are actually techniques of projecting images in a such way that they could help drawing, artists, illustrators, painters.

Now, the apparatus that we know - the lens, the medium, the sun or any other light source - is being extended into the realm of computing. Apple a while ago bought an Israeli company called LinX that makes a technology which will be used in the next iPhone. It will have at least two lenses that will take multiple photos which are sent to a data centre that then process the final visual result. I mean, these camera phones are quite shitty, so they use algorithms to overcome the laws of physics that are currently limiting them. So the image gets 'made' in the machine, this is what ‘computational photography’ is, and this will be the next big step.

What do you feel when you encounter tech companies 'overcoming the laws of physics' ? Well, not really overcoming, more like finding smart ways around them. Just to stick with the conversation about photography - it's a conservative field in a way - and I'm not talking about smart phones but about German, and then Japanese camera manufacturers, paradigms of making the single-lens-reflex camera; about the history of Robert Hooke, the inventor of the microscope. Canon, Nikon, are very skeuomorphic in the way they go about making cameras and their idea what a camera is supposed to be.

A Finnish friend who recently visited Tokyo told me he feels that in Japanese corporate culture, these things are hard to overcome structurally. The approach that you make gradual improvements to existing technology – in this case, the camera – is destroying their traditional businesses because in California they work totally differently. They don't have any inhibitions about changing the paradigm completely; it is about ‘disruption.’. And if one company does not do it, another start-up will be right there to do it instead. A traditional company like Nikon or Canon cannot change so quickly or radically.

The same may happen to the German car industry, for example, because they cannot see beyond the combustion engine or the primacy of the human driver. I mean, look at Tesla, they don't give a damn about those aspects…or maybe even they are too conservative? There are so many things you can imagine that can work differently. Is a car something on four wheels that goes from A to B? Or is it something else? And this is going to affect large corporations that are important in the economy all because they don't get the magnitude of the shift. It is an existential threat to them, actually.

For me this is relatively easy to see now with respect to photography; I can because I have thought about it a lot. But still, I didn't anticipate the scale of the current shift back in 2006.

So it is kind of obvious what is next – any thing that can be emulated by a Universal Turing Machine, which for cameras is easily imagined, will be. It's the same for cars. Not that the car will become digital, but it will get sucked into the same sort of platform paradigm. You may believe that you have a smartphone holder in your car, but it actually is a car holder for your smartphone. The key thing I am getting at is that the network – and the knowledge that is embodied in the networked – is paramount.

The practice of making images has been undergoing this shift, and I did too. I was really resistant to Instagram initially because the quality was really bad. But lately I have fallen victim to same thing that I mentioned, that the networked nature of the photo has become more important than the quality of the photo itself. I was a kind of a last holdout at Flickr, I guess. I would have a camera on me at all times, a good camera. But at some point, people would start to say to me “what are you doing, you can’t upload the images until you get home.”

We're at a place now where humans and machines can be pretty responsive to each other. Machines can enhance and augment human functions and desires quite well. For example, the selfie, can become so much better, and as the photographer, you can manipulate how you want to be represented because the software is programmed to respond to what you may want to do to improve the image. What do you make of this in terms of what it means for photography? Photography has become sort of a non-skill; everyone is a really good photographer now and has spent time looking at, taking and editing images. People who are twenty years old now laugh at people who say they are photographers. A group of my students at UC San Diego who were making a film for a project and took out a really expensive video camera but ended up shooting it on an iPhone 6S. The iPhone was ‘smarter’, the quality was better, it lowered the threshold for them to actually make a film. And they made an amazing film without needing certain skills.

I do think that people are actually more skilled now in what used to be specialized, for example, video editing. When I studied in Berlin, in the early 2000s, no one knew video editing and they were like “wow” when people were working with moving image. Now it is so banal to record clips and edit them, you can do it right on the phone. What people are using with Instagram is almost equivalent to a professional photo editing tool like Lightroom that Adobe charges you three hundred dollars for.

Do you take photographs? How do you take photographs? I take the same photos I was always taking. I would edit them a lot, as I would edit in a dark room. So the final thing that got me into Instagram was when the high level editing features became accessible, like straightening pictures, sharpening, adjusting levels. I work on my images as lot, but in an old-school way. I never use filters, of course.

Why not? Again it's a skeuomorphism, it's a mock analog technique. I see why people do it, but I don't like this nostalgia effect. I am more interested in a technically good photo.

Tactical Tech included Buttons in 'Something to Hide', which to me is the most curious and interesting of the three tables in the White Room. Can you talk a bit about Buttons and its relationships to the idea of 'Something to Hide'? The funny thing is that Buttons is like a black box that takes something from you. It takes a photo that is actually just metadata and gives the network this metadata. The idea of hiding is interesting; it's connected to you pressing the button, hiding behind the camera. When I was creating Buttons, we sucked so many images from the network just to test it. But it is not active hiding; you will never know what the image that you will get is. You press the button and something appears, and what it means will be forever obscured. People upload really strange stuff and you just don't know what it means. Also the box physically obscures, because you are not in charge of the technology. So, this thing is taking something from you, and giving you back something that is unknown or obscure or confusing, it’s not what you were expecting, possibly.

Back then in 2006, Buttons ran off a central server; now there is an app and if you switch it off, then the image disappears. It's somewhat like Snapchat in this way, but you typically know from whom a photo or a video on Snapchat is coming from - with this you don't know. So yeah Buttons complicates the idea of what you are showing and you are hiding.

What did you think of the whole exhibition, Nervous Systems? Which pieces did you like? Did you find any connections between your work and that of others'? I wish I remembered everything from what Anselm [Franke] said in his tour– he gave a dense and amazing walk-through yesterday. The exhibition design is stunning, it's the first thing I thought when I walked in, it looks futuristic, with the poles and lights, and something like this can go many ways but in this case it really works. It's very thorough and it reflects on itself.

Quantification and its processes I am familiar with and it’s a different world view totally. The social is not just people and relationships, but also the political and the structuring of society. Quantification has gone on visibly and invisibly. There are other works that also talk about metadata. Matteo Pasquinelli has a triangulation [in the show] that talks about “not spiking the algorithm” which refers to this idea that we don't want to give away certain things, certain information to the network. He refers to the means of self-control that people have, such as not asking certain questions to Google because they know those questions are being recorded, and have political connotations. This could put them on a black list if discovered in the wrong context. This is also pertinent to photography in a way, because some people are savvy and would know when to switch off geo-tagging, or when to not take a photo at all. People have become aware of what they take because they know it is a networked practice.

I also liked the piece about the stock market modeling by RYBN.org, Algorithmic Trading Freak Show since I'm quite interested in modeling and there is a notion that financial models are so bad that their predictions are hardly better than randomness.

I really liked Melanie Gilligan's video piece The Common Sense; the work is really good in how it is thinking through things with very minimal means. The trick of sci-fi is to show you a future and then inject certain plausible situations, forcing you to face their consequences. It's like, right, let's take this thing, this technology in this case, and take it to its logical conclusion; what happens if it would be deployed on a large scale, adopted by almost everybody. It's a dystopia of course, and dystopias are somewhat easier than utopias; but a good dystopia can be worth a lot. Like what Charlie Brooker does with Black Mirror.

A final question. Since so much of Buttons is about a particular moment in the emergence of Web 2.0, do you think you could or would do an update of Buttons? What would something like Buttons mean now? Well, I guess I would make it run on Instagram – it's more appropriate and relevant now. It would all be faster now, I guess, in 2006 it sometimes took hours for an image to appear, which was also nice in its own way. It kind of reminded you of the old days, waiting for an image to be developed.

If I made a project on photography it now, it would have to be about this post-optical future, but then it would be a totally different thing. You could imagine actual cameras that don't use lenses but use something else completely, you would take photos without ever taking a photo. There are so many ways of capturing and inferring information about the visual. And there is a deep learning project where you take a picture, a random picture of some turd on the ground, and one or two seconds later, a neural network identifies where the turd is, which street, because it knows the world so well. If you let an algorithm like this loose on Google Street View it would un-hide everything. The whole city and any part of can be located immediately with very little data because the knowledge is embodied in the network – this was fiction at some point, and now it is really hitting the scene. It isn't really photography per se but it is, actually, its logical progression. I cannot imagine that any camera companies are onto this, but I am absolutely sure that Apple and Google are.

So you will have more of the these algorithmic techniques integrated into the body of the optical, or the para-optical and the more this gap widens, the more you will have two very different things completely. One stays static, and the other goes off into something that seems alien yet is very much in line with the past 300 years of the history of knowledge.

This interview was audio-recorded and edited for length and clarity before publishing.